With Axis forces surrendering in 1945, the company’s leadership felt that the WPB would soon grant permission to use the new facilities and begin manufacturing building products again. Coxe, who often wrote letters to the board members and many others, said in a letter, “If the circumstances in Europe are no worse by late February (1945) than they are today, I believe that the War Production Board will give us a directive for our second quarter allotment as we requested”. His prediction proved correct; in May 1945, the

WPB removed restrictions on the amount of lath manufacturing that could be completed as well as removing rationing of steel purchases. In June, the new office on Fayette Avenue opened. In July, the plant opened for production in its current location. Coxe wrote in another letter to the Board of Directors:

“For your information, the War Production Board limitation order on the manufacture and sale of metal lath was revoked in its entirety on May 10th. This means that we do not have any restrictions as to the amount of lath we may manufacture nor do our customers need a priority to purchase our materials… I might add since the revocation of our limitation order, we have received by telephone, telegraph, and letter sufficient orders to consume our present capacity output through December of this year.”

Early the next year, Horton reported that “…for all practical purposes our entire production for the year 1946 has been sold and approximately half of 1947 production has been sold”. The company began using railway shipping to deliver to customers in order to move larger amounts of material more quickly than they otherwise could. Waiting periods for customers had grown from weeks to over a year. Marketing the product line was not necessary as demand was increasing exponentially; however, in July 1946, the Alabama Metal Lath Company’s Board of Directors approved $5000 to be spent on the company’s first advertising efforts. Advertisements were placed in the Sweets Catalog, The Building Material Dealers Magazine, and other places.

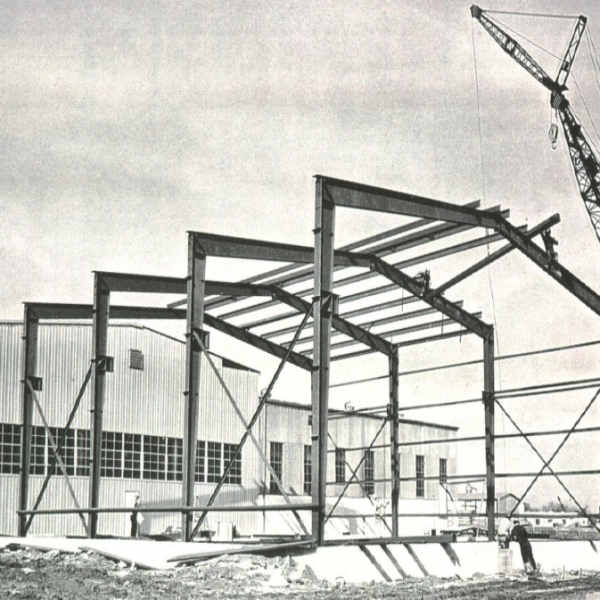

During these years, the company unloaded railcars full of raw material. One day, while the plant manager was not present, the employees unloaded all of the material from one side first, causing the railcar to become unbalanced and flip over. It took a crane to right it again.

In 1949, the company added roof drainage products to the product mix in an effort to broaden its offerings so as to become less dependent on the new construction business. About 50 percent of the sales of those products were used in repairing existing structures, and the other half was used towards new construction. Diversifying the product line helped shield the company from negative changes in new construction.

As the 1950s began, with little available capacity, the company did not pursue new products. Towards the end of that decade, the company had begun to explore new products to expand on the idea that brought it to existence. In 1956, Frank Horton decided to retire and John Coxe became president of the company and prepared the company for its coming expansions. In the late 1950s, an industrial engineer was hired for the purpose of conducting time and motion studies to assess the company’s operational efficiency. This helped drive cost out of the product and improve profitability long before LEAN principles became widely used to achieve these goals.